The Looking Cure: John Hofsess’s The Palace of Pleasure

Art & Trash, episode 12

The Looking Cure: John Hofsess’s The Palace of Pleasure

Stephen Broomer, May 9, 2021

John Hofsess’s The Palace of Pleasure emerged from the psychedelic haze of 1960s postmodern art. It was a blistering work that combined arresting abstract-imagery with the wounded expressions of a young couple, edited into a collage of mass culture imagery and album and book jackets, all of it framed as a therapeutic treatment. Addressed to a generation coming up in an era of protest and social change, where many found themselves increasingly burdened with hopelessness, paranoia, and neurosis, The Palace of Pleasure was offered as a cleansing ritual, a post-Freudian expelling of dammed-up energies that anticipated The Primal Scream. In this video, Stephen Broomer discusses Hofsess’s therapeutic ambitions, how the film was composed from Hofsess’s earlier films, and the sensual spell of the work, the way in which it commands us to enter into a universal fellowship of touch that circulates, from us, to us, through us, to strain the boundaries between the self and the other.

The Palace of Pleasure was digitally restored in 2008 and again in 2016 by Stephen Broomer in consultation with John Hofsess, Robert Fothergill, Peter Rowe, and others involved in its production, and through the facilitation of the Library and Archives Canada and staff of the Gatineau Preservation Centre, with special thanks to Greg Boa.

SCRIPT:

John Hofsess’s The Palace of Pleasure emerged from the psychedelic haze of 1960s postmodern art. It was a blistering work that combined arresting abstract-imagery with the wounded expressions of a young couple, edited into a collage of mass culture imagery and album and book jackets, all of it framed as a therapeutic treatment. Addressed to a generation coming up in an era of protest and social change, where many found themselves increasingly burdened with hopelessness, paranoia, and neurosis, The Palace of Pleasure was offered as a cleansing ritual, a post-Freudian expelling of dammed-up energies that anticipated The Primal Scream.

In 1965, John Hofsess formed a campus filmmaking club at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. In this conservative setting, Hofsess’s underground films courted controversy and were met with ridicule and suppression, but they fared much better with international audiences and critics. The Palace of Pleasure would be Hofsess’s definitive work, a cycle containing all of his creative activity in this period. It casts the critical eye of post-Freudian analysis on the politics of the era, free love, the peace movement, taking inspiration from Wilhelm Reich’s theories of orgone energies and the function of the orgasm, from Norman O. Brown’s Love’s Body and Life Against Death, from Herbert Marcuse’s Eros and Civilization, from Paul Goodman’s Growing Up Absurd. Palace of Pleasure is rooted in these works, and in Hofsess’s broad readings in modernism and his opposition to what he believed to be a central hypocrisy inherent within the counterculture of the sixties. Hofsess’s reluctance towards the free love and peace movement is evidence of the film’s critical operations, and his art is a method, a prescription to discharge all of the old and inherited neuroses, through an immersion in coloured light and sensual imagery. Hofsess devised an aesthetic theory for what he was doing: he called it cinematherapy.

Hofsess began making films with the conviction that modern art, music and poetry often had an inbuilt multiplicity of experience and meaning that was seldom present in cinema, and that this polyphony was a thing which, out of all of the arts, film was best suited to realize. The most direct inspiration for Hofsess’s filmmaking was Andy Warhol’s multimedia show The Exploding Plastic Inevitable, which Hofsess had been involved in bringing to McMaster University as part of their arts festival. For Hofsess, it was a formative encounter; an immersive experience, in which coloured lights, slides and movies were cast on dancing bodies, and the Velvet Underground improvised against distorted speakers playing Motown singles. It was the grand utopian set of the New York underground, a sensory deluge, its frames dense and multiple, a new media ecology.

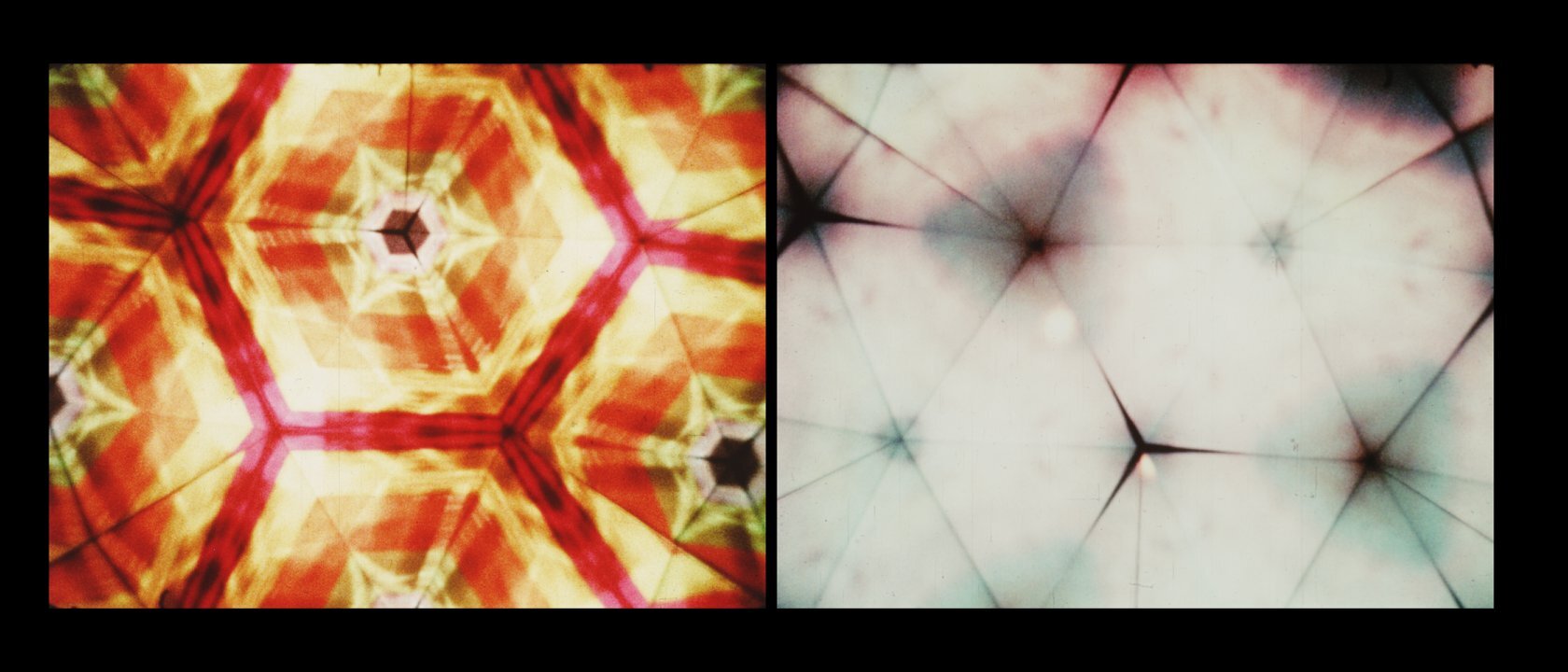

Hofsess’s first film, Redpath 25, made in 1965, had featured tin foil, cream, rose petals, ferris wheels, and flesh, all set to The Who’s stuttering, ironic anthem, “My Generation.” A young woman dreams herself into a psychedelic space of coloured light and tin foil. Peeling the foil back, she reveals her dream lover. The two caress and embrace, intercut with imagery of a carnival, a fountain, and lights reflecting on foil. The dream lover’s face is fractured and reformed by nail polish applied directly to the film strip. Redpath 25 was a direct response to the notion of a third eye cinema that Hofsess had encountered through Jonas Mekas, the idea that one could create metaphors for interior experience through the abstraction of the film frame, bringing the film closer to patterns of consciousness and perception, to invite meditation and reflection. Hofsess’s second film, Black Zero, introduced another screen into the mix, a diptych dominated by kaleidoscope images, made by rephotographing footage from Redpath 25 and other dramatic scenes that feature elsewhere in the film. Much of the film is composed of scenes from the unhappy domestic life of a young couple, as well as scenes of a symbolic threesome that seems to illustrate Leonard Cohen’s poem “The Lovers,” with a recording of Cohen reading it on the soundtrack. In these scenes, three figures lay in bed together, two men and one woman; one of the men appears sad and distant, unable to enter into this union, as if he has become the “you” of Cohen’s poem, a witness to, and only later a participant in, epic love—“You climb into bed and recover the flesh, / You close your eyes and allow them to be sewn shut….”

Black Zero’s debts to Cohen’s poem are also strongly related to its function as a synaesthetic work, one that specifically connects touch and vision, a film that desires to summon in viewers a sense of full-body participation in sensual reverie. This work commands us to enter into a universal fellowship of touch that circulates, from us, to us, through us, to strain the boundaries between the self and the other, as in Cohen’s poem when he writes, “Her hair and his beard are hopelessly tangled, / When he puts his mouth against her shoulder / she is uncertain whether her shoulder has given or received the kiss…” This is the nature of the film’s erotic energies, which reconcile with its social critique. Its most provocative images are of kissing and caressing, the circulation of sensual energies through touch; and they stand in a sharp contrast to scenes of menacing rituals, violence, and the couple’s uncertainty, their tearing, pensive eyes.

Redpath 25 and Black Zero would be presented together as The Palace of Pleasure. The Palace of Pleasure was conceived as an ultimate, modular film, one which Hofsess could continuously build upon, adding new segments over time. The project had been planned as a trilogy, but only these first two parts would be completed. When Redpath 25 was presented as the first sequence in this new form, it had a second screen added to it, this one featuring news footage from the war in Vietnam, so as to allow it to seamlessly transition into Black Zero, and to offer a jarring contrast to the dreamer’s tender fantasy. A proposed third part was at times referred to as Movember, and was said to be inspired by the aesthetic experimentation and euphoria of Huysman’s Against Nature; elsewhere it was referred to as Resurrection of the Body, with debts to Norman O. Brown’s Love’s Body. Brown, an essential thinker of the era, offers, with allusions to Holy Communion and to Yeats, that “the true body is the body broken.” Hofsess’s sources and titles suggest that he intended a work in which the body is broken—broken like the eucharist, broken like Osiris—broken before the dreamer can dream of renewal or resurrection, to dream themselves into a body that is humbled but perfect.

The Palace of Pleasure integrates multiple presentational forms. In Redpath 25, it integrates this fantasy-drama with chemical abstraction and, through its adjoining screen, this passionate reverie is met with harsh documents of war. Black Zero introduces kaleidoscopic rephotography, dramatic scenes which stage a ritual sacrifice, an unhappy domestic life, a frustrated threesome, and throughout, images from advertisements, the covers of books and albums, and other formally imaginative interruptions. These different styles are reconciled within the film as a core polyphony. Where Andy Warhol’s dual-screen feature, Chelsea Girls, bears the philosophy that if you’re going to look at one image, you might as well look at another, Hofsess’s dual screens are interwoven as if to provoke reflection from one image to the other. In this they function almost at random, but they also serve as a digressional system. Their aim is to overwhelm the viewer, for that is Hofsess’s central prescription, to fill the eyes and the mind up with more material than can readily be sorted on first glance. It demands a particular sort of commitment on the part of the viewer. This form collides with Hofsess’s therapeutic ambitions such that the film might be taken as an act of hypnotism or, more in the spirit of participation, a seance. In The Palace of Pleasure, this form reaches its greatest density in the final sequence, as the image becomes more elusive and violent, accompanied by the Velvet Underground’s “I’m Waiting for the Man.”

While Black Zero was in production, Hofsess wrote a production diary that was published in the Canadian film magazine Take One. The piece, entitled “Towards a New Voluptuary,” argued for a Brechtian approach to dramatic editing that would flatten out an actor’s performance; and for an integration of persuasive models of rhetoric into experimental film form, persuasive models being roughly equivalent in Hofsess’s estimation to his sensually-involving hypnotic style. His rhetorical film form would emphasize repetition, bright colours, flickering or pulsing light. Hofsess’s intention was to edit dramatic scenes in such a way as to reshape the performances of actors into pure affect, so that rather than identify with the drama of their characters, the viewer would recognize their performances as archetypal masks. Hofsess’s goal was to mix this approach with temporal elongation, abstract imagery, and an atmosphere of sensual pleasure such that it would draw the viewer into a state that would allow them to disassemble and rebuild themselves. He held this in contrast to work like Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures and Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising, films that he saw as transgressive without constructive gains, anti-persuasive, as if persuasion was ever a value to which Smith or Anger aspired. Hofsess’s therapeutic vision for cinema is governed by a motivation to heal others. And in a sense, he was also turning the movie camera into his own ideal post-Freudian therapeutic machine, where he could be both doctor and patient.

When Palace of Pleasure was at the height of its circulation, Hofsess abandoned his plans to make a final sequence and complete the trilogy. Instead he chose to make a feature-length experimental dual-screen adaptation of My Secret Life, an infamous Victorian-era erotic diary. The resulting film, The Columbus of Sex, led to Hofsess and his producers being arrested and put on trial for obscenity. While Hofsess was not convicted due to a technicality, his producers were, and the film was subsequently banned. The producers sold the film’s elements to the American genre filmmaker Jack Harris, who had a habit of buying and re-editing student films—as he had with Dennis Muren’s Equinox the same year. Columbus of Sex thus reappeared in the commercial market, re-edited and featuring considerable newly-shot material, as a single-screen piece of softcore erotica.

With Columbus of Sex debased by its producers, the surviving sequences of Palace of Pleasure are the best existing representation of Hofsess’s theory of a therapeutic cinema, one in which the ideal spectator could experience a baptism by fire, emerging cleansed of hangups and heartaches. Hofsess’s treatment was not a cure so much as it was an opportunity for self-exploration, its lights bursting through our eyes to illuminate the recesses of our skulls.