The Wrestler’s Cruel Study: Theatre and Honour in Pushed Too Far

Art & Trash, episode 14

The Wrestler’s Cruel Study: Theatre and Honour in Pushed Too Far

Stephen Broomer, May 19, 2022

Jack Rooney's Pushed Too Far is an action movie built on an allegory of good and evil: karate school owner Tom Ford (Herbert Johnson) is challenged to a fight by professional wrestler / spree killer / fugitive William Otis "The Bear" Kelp (Mike Clark). What follows is a battle of wills, Ford's noble restraint contrasted with The Bear's sadistic abandon. In this video essay, Stephen Broomer examines the character of The Bear, his gruesome theatricality, and the character of the town—Greenfield, Indiana—host to the spirit of mid-1980s Americana.

Pushed Too Far was issued on VHS tape in 1988. It is presently available on DVD via mail-order from www.hoosiermovies.com

SCRIPT:

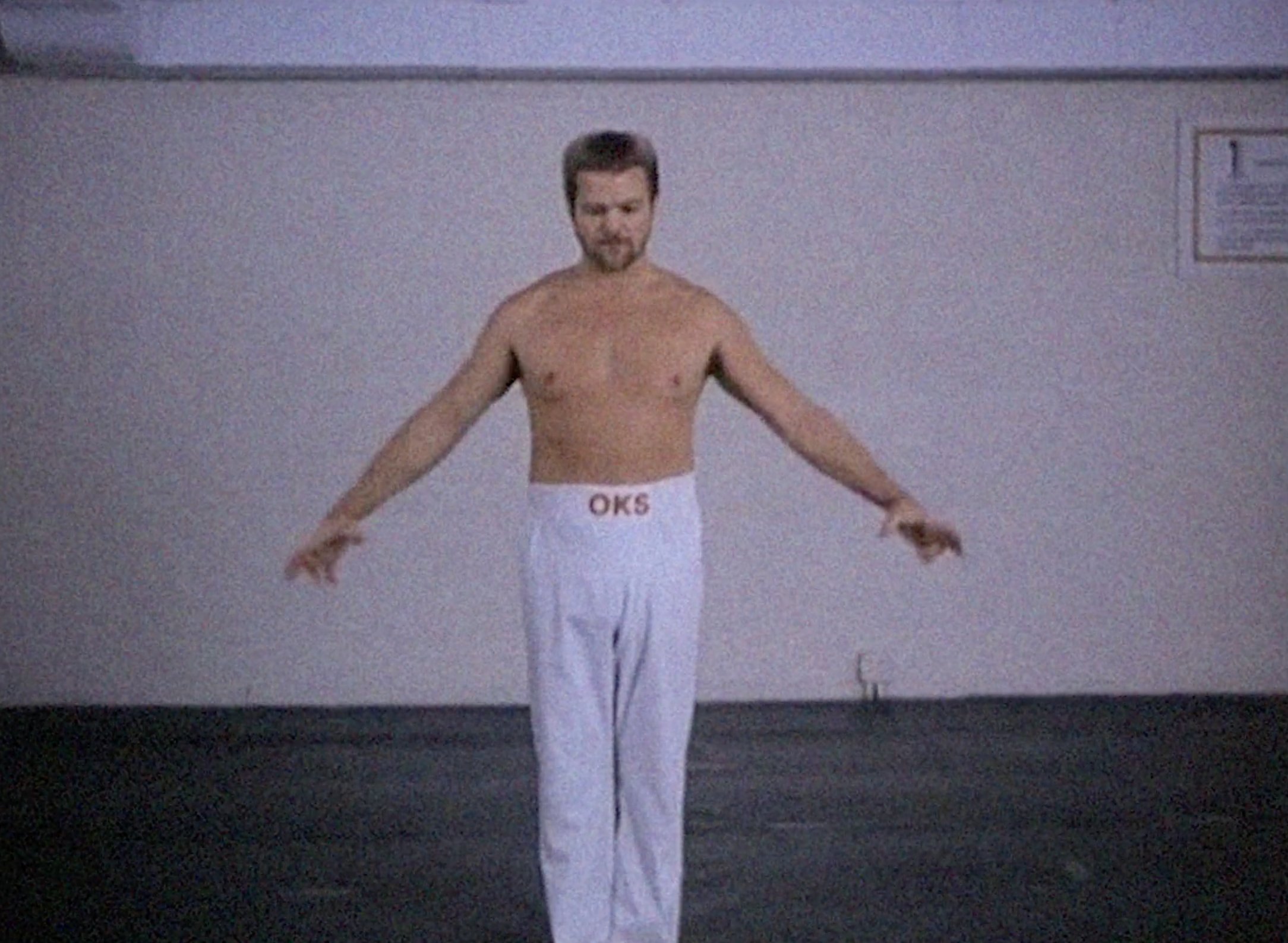

All the world’s a stage. Or is all the world a ring? In Pushed Too Far, a former professional wrestler, the Bear, now a dangerous fugitive, lurks in the woods near Greenfield, Indiana, stalking and killing the townsfolk by putting them in his trademark bone-crushing holds. The boundary between fantasy and reality is already under distress early in the film, as the threat of the wrestler is equal parts athletic and dramatic, recreating the theatricality and the spectacle of the ring as he cuts a path of destruction through the town. Pursued by police, he vanished into the woods years earlier, becoming a boogeyman, and, like his namesake, a predator. How the Bear has survived in isolation is never explained. He claims he seeks a challenge—but his problem, to paraphrase Freddie Blassie, is that the locals are nothing but pencil-necked geeks. The Bear is a figure of tremendous violence, not merely as a force of nature, but also as a doubly fictional construct that’s escaped the violent fantasy of the ring and transposed itself into the surrounding world.

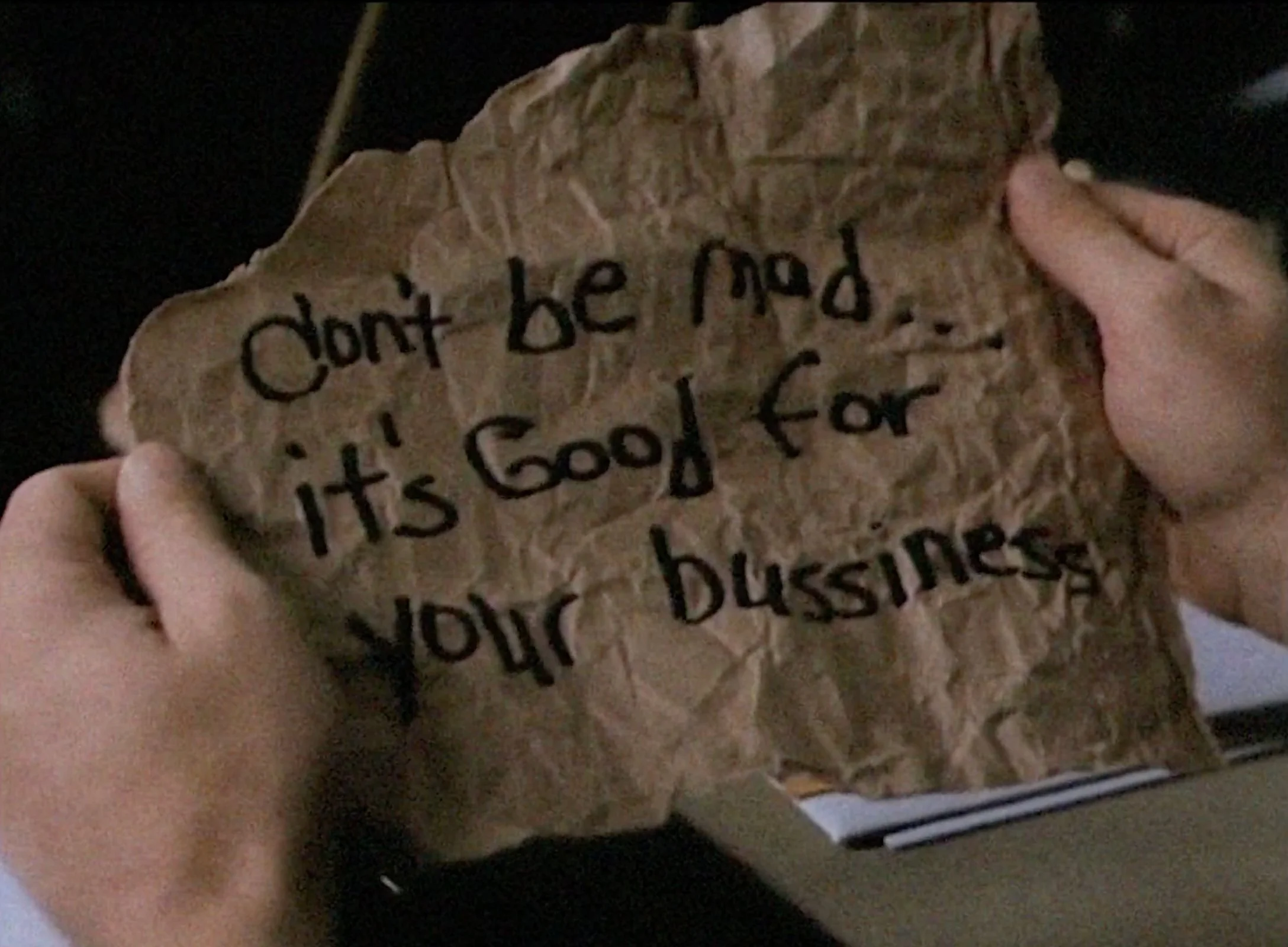

But the Bear’s motives—his preoccupation with the spotlight, his histrionic pursuit of supremacy over others—are minor aspects of the film, which, for the bulk of it, focuses instead on the danger he poses to the peaceful life of the town’s karate teacher and his family. Tom Ford owns a local dojo, where he follows a strict philosophy of non-violence. He finds himself targeted by the Bear as a worthy challenger. The nobility and honour of eastern martial arts philosophy is placed in conflict with the stage spectacle of western entertainment. The Bear is drawn to Ford’s pacifism, as it allows the wrestler to make grand, theatrical provocations. Ford’s refusal to meet the Bear’s challenge results in a series of violent killings, of his son’s friends and of his own wife. Ford is reticent to get involved, even after the murder of his wife, who is remembered in a idyllic montage. His hesitation forms the central conflict of the film, as he is urged to take revenge, first by his son, then by a masked ninja, full of strange oaths, who has invaded his dreams on horseback, offering a sai. In another strange violation of the film’s sense of reality, Tom Ford wakes to discover ninja weapons have materialized in his bedroom.

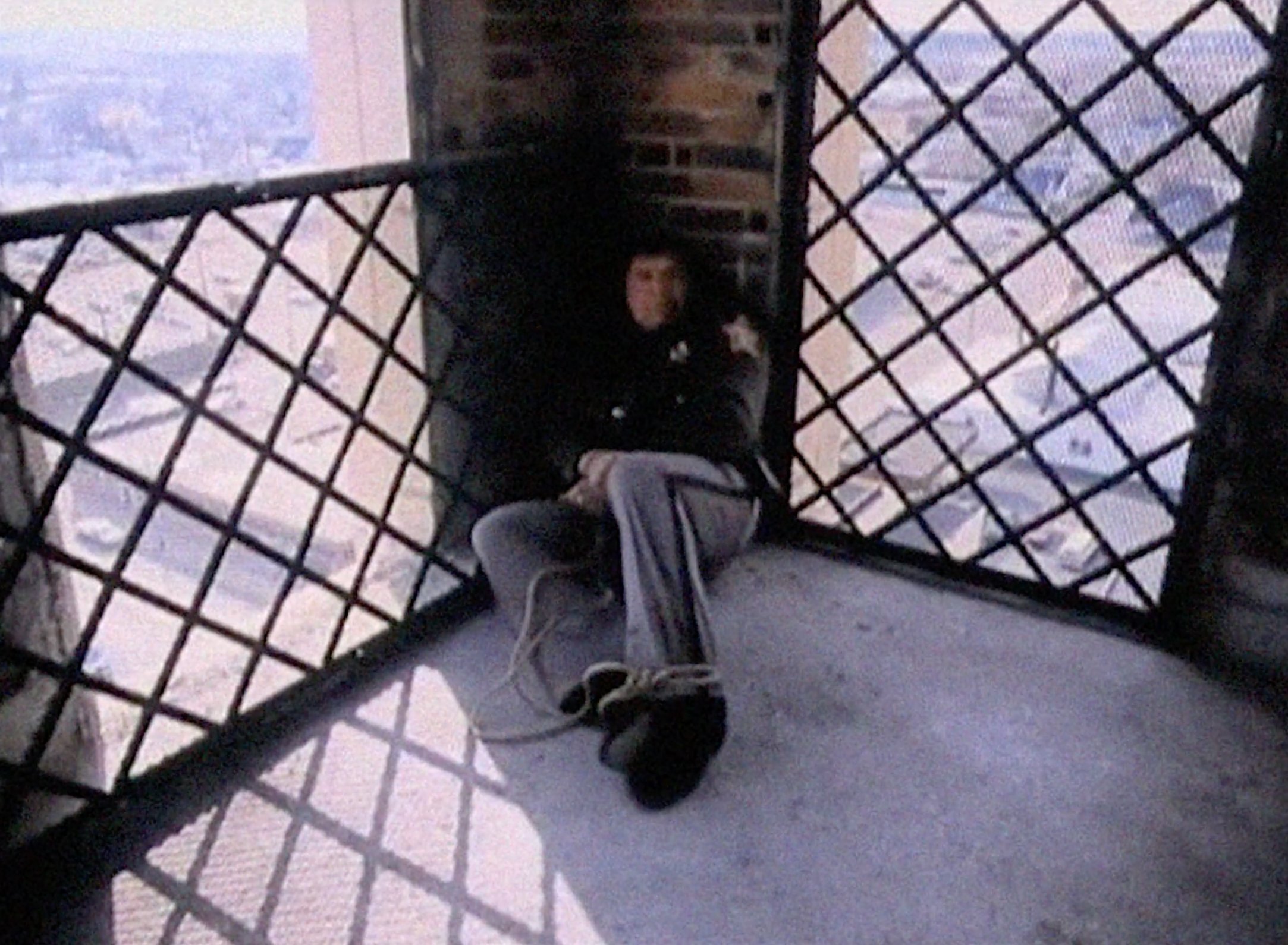

The ninja’s appearance spurs the film’s climax. The Bear attempts to shoot up the town’s annual street festival from a clocktower, an event which in itself is a contradiction of his methods, shifting from the physical confrontation of the bear hugs for which he’s named, to sniping targets in the American tradition of Charles Whitman. “One man in his time plays many parts.” This strange indirection seems to disavow the Bear’s fixation on physical contest: it suggests that this challenge was never about might, but about theatricality, and there is no greater act of participatory theatricality than attacking the audience. The Bear’s attempt at a mass murder sees him cross from the Brechtian self-consciousness of American pro-wrestling to the brutality and sadism of Fernando Arrabal and le Mouvement panique. The Bear is dispatched in a manner equally theatrical—by the sudden appearance of a masked, costumed vigilante. The ninja has stepped out of Ford’s dreams—and, it’s implied, into his body—only to vanish after saving the day, allowing Greenfield to return to normal.

Personal and community responsibilities define that normalcy. Ford’s dojo, for all the comedy of its weakly synchronized choreography, is a symbol of communal health. By contrast, The Bear represents pro-wrestling as a sport of triumphant individualism. The film is a prolonged tribute to the community of Greenfield, Indiana, culminating in the Festival Days sequence—intercut with the Bear making his sinister preparations—a sequence that is as affectionate toward Greenfield’s present as it is nostalgic of Greenfield’s past. Greenfield is fully realized as a place; a dull, sleepy place, perhaps, the kind of place where dojos became a focal point for the health and wellbeing of growing midwestern communities in the Chuck Norris epoch of life in the American heartland. In developing the world of Greenfield so authentically, its endurance becomes the final triumph of Tom Ford’s pacifism over the Bear’s violent hungers, a triumph of community over the gloating melodrama of the ring.

CREATOR’S STATEMENT

American karate has a fairly long history, stretching back to Robert Trias and other servicemen who drew from their experiences in the Pacific theatre of the Second World War to create something between a spiritual-athletic movement and an industry. While it may have grown to be a widespread phenomena by the 1960s, with its own regional tournaments, its own leading teachers, and its own distinctive customs, it was thanks in no small part to Chuck Norris that dojos became, through the course of the 1970s, a staple of recreation and health for an America weened off the myth of the west (John Wayne, Randolph Scott, and all that) and pointed towards martial arts as something less distant and exotic (as with Bruce Lee) - a thing practiced by a guy who looks like he could work in your neighbourhood hardware store (Norris). There are aspects of this culture shift that speak to Orientalism and appropriation, or to shows of physical strength as a means of maintaining white hegemony. But on its surface, as was surely true for the bulk of its participants, the American karate movement was essentially utopian: another means of refining the self, of moving with purpose, even, a response to the queries of Paul Goodman as to what makes for a meaningful society.

Pushed Too Far is a great example of the degree of influence Chuck Norris and the community dojo movement had on midwestern American culture in the 1980s. The film is modelled on a traditional Norris set-up: a decent man, reluctant to violence, is forced to confront and dispel a violent criminal (be it a gangster, a serial killer, or, in one memorable instance, some kind of Frankenstein monster). There are passing amusements in its structure, of the usual kind—maudlin flashbacks, campy acting, and strange montages of average-joe karate training—but what sets it apart is its regionalism (a proud Hoosier setting) and the nature of its conflict (pitting the humble discretion of American karate against the theatrical artifice of professional wrestling). In this video essay, I’ve focused almost exclusively on the villain, The Bear, barely seen, whose booming stage voice, whether in winking intention or by campy accident, is the first sign of the film’s caricatured mockery of Pro Wrestling, another American ‘battle entertainment’, scripted, staged and populated with outlandish, iconic characters. The film’s world seems to understand The Bear as an immensely strong actor for whom the boundaries between reality and fantasy have blurred: but it never comes right out and dismisses Pro Wrestling as fakery. Instead, The Bear’s flamboyant demands broadcast the distance between his morality and Tom Ford’s. The Bear’s final transformation from street fighter to sniper serves as the film’s indictment of wrestling, and of theatrical, flamboyant, performative warfare.

I made this video essay in the last weeks of March; but I post it only five days after a hideous, racist mass shooting. The events in Buffalo are, sadly, business-as-usual for America. Racist violence happens here in Canada, just as it happens all over the world, but in Canada, we don’t give kids guns as Christmas presents; we don’t make it so you can buy a semi-automatic rifle to ‘hunt deer’; we don’t have what I call in this video essay “the American tradition of Charles Whitman.”

I give this digression only to say: in presenting a video about a film that features a mass shooting as one of its major plot-points, I am not trying to be topical, nor would I self-censor. For the sake of viewers who have been caught up in this news cycle, or who live too close to this kind of violence for comfort, I offer this content warning: this video refers to and shows scenes of a fictional representation of a mass shooting.